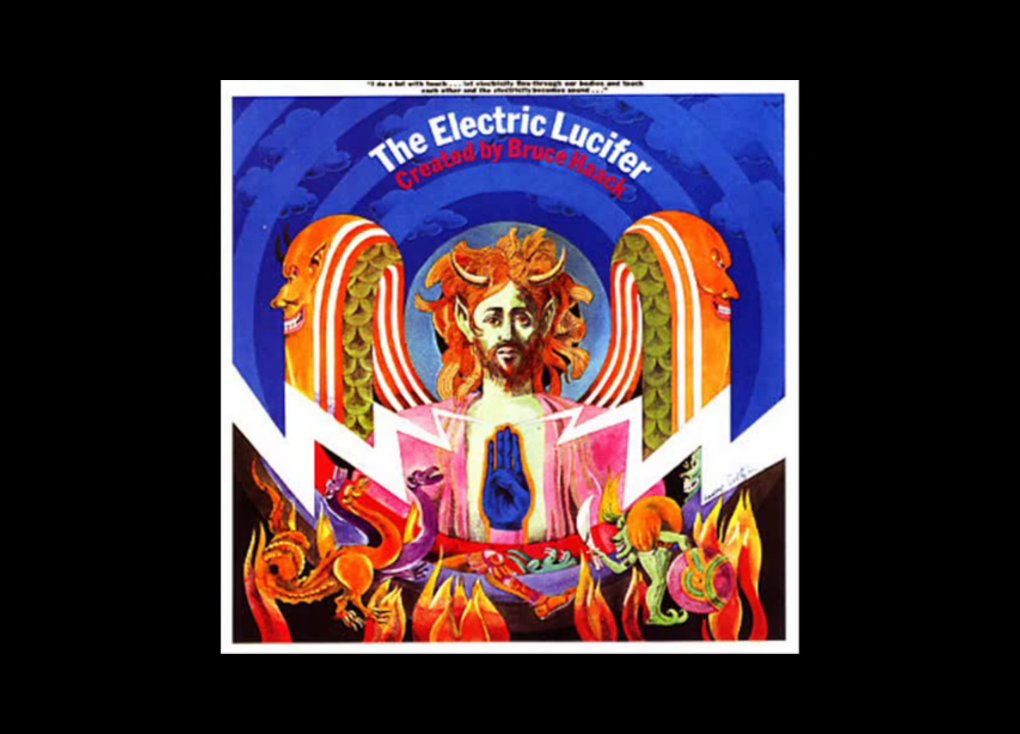

It was only a matter of time before a Monday Magick entry focused on one of the most important, and most original, Illuminist/Gnostic philosophers to ever grace the music industry, electronic alchemist Bruce Haack. His 1969 Columbia Records LP ‘The Electric Lucifer’ was one of the boldest statements, both musically and metaphysically, in the history of modern “popular” music. I profiled it in these pages several years ago after discovering Haack, here’s an excerpt…

A quick Google search brought immediate results in the form of a fan-page with a description of the LP and excerpts from the liner notes (which the author of the site describes as being quite similar in style and tone to a Dr. Bronner‘s bottle), a photo of the album cover (pictured above) and the name of the artist responsible for the album’s creation, Bruce Haack. I had never heard of Haack, but with the trippy cover artwork and allusions to the album’s blend of ahead-of-it’s-time synthesizer technology and out-of-this-world philosophical content I was determined to find out more about this mad musical scientist and if I could, get my hands on his only major label release, 1970’s ‘The Electric Lucifer.‘ A little more searching turned up a wealth of information which would seem to indicate that Haack, who had a dysfunctional childhood in rural Alberta, Canada, was some sort of unrecognized genius-savant. He reportedly showed a gift for music from an early age (he was giving others piano lessons at age 12), played in bands throughout his teens, hosted his own radio shows, earned a degree in Psychology from Edmonton University and eventually attended Juliard on scholarship before ultimately dropping out to compose music (which incorporated forward-thinking electronics and tape-samples), build his own instruments and develop his unique socio-spiritual philosophical concepts.

Which is really where ‘The Electric Lucifer’ comes into play. As a suite of songs it’s not unlike the boroque jazz-fusion rock-operas David Axelrod composed both for his solo LPs and his work with the Electric Prunes. What distinguishes Haack’s ‘The Electric Lucifer’ from Axelrod’s tributes to William Blake, environmental warnings set to music and modern re-imaginings of Catholic masses though is the fact that Haack’s music is almost entirely electronic and far more original in it’s immediate social message and universal metaphysical purpose. I know, you’re probably thinking “big deal, he made electronic music.” But what you’re failing to realize is that he made almost entirely electronic music in 1970, a time when things like synthesizers and drum machines were still virtually unknown, and that he did so using synthesizers which he mostly built entirely himself out of cheap commercial components and household appliances! Bruce Haack had no formal knowledge of electronics, yet he built a number of his own, totally unique, electronic instruments bearing such fanciful names as The Magic Wand, The Dermatron (a synthesizer that allowed the human body to be played as an instrument by leading an electrical current through skin contact with another person) and the People-odion. He even built and used his own 12-voice polyphonic synthesizer (it can be heard on ‘The Electric Lucifer’) during a time when the widely available commercial synthesizers other brave musicians were using (he was using them too), such as the legendary Moog, were only monophonic. His mastery of these electronic instruments is evident throughout ‘The Electric Lucifer’ as songs drenched in intricate synth textures, manic keyboard melodies, bouncing analog basslines, sweeping electronic noises, crunchy drum machine beats and liberal use of the vocoder pour out of the speaker awash in dubbed out tape echo, lending the whole project the feeling of some plug-in infused masterpiece of modern day lo-fi lap-pop electronica. The wholly electronic nature of the album’s soundscape (which prefigures everything from Kraftwerk to Zapp, Radiohead to Daft Punk, J. Dilla to Postal Service) is so thoroughly ahead-of-it’s-time that you might actually have a hard time believing it was released before most mavens of up-to-date electronic music were even born. Take into account that some time around 1968 Haack allegedly expressed to a personal friend his belief that there would be “a time when all people would create and share their music ELECTRONICALLY without record company involvement” and the man’s ability to foreshadow the future (which puts me in mind of Nicola Tesla in a lot of ways) becomes a little scary.

This neo-futurism is reflected in the subject matter of the music found on ‘The Electric Lucifer‘ as well, which blends metaphysics and electronics into an apocalyptic stew which may in fact be the only thing that can prevent war and destruction, not just here on Earth, but across the universe. The basis of the album is a simple anti-war, pro-love, humanist philosophy Haack called “Powerlove.” But it’s backed by a slightly more complicated eschatological mythology (which incorporates traditional Judeo-Christian religiosity, various world religions and mysticism while reaching towards the ideas expressed in the “ancient astronaut” theories of Erich von Däniken and Zecharia Sitchin) involving “the Lucifer people” being forced out of heaven (or off of another planet according to the liner notes) only to reside here on Earth. It’s not clear if we, as humankind, are in fact these “Lucifer people;” children of the heavens given a place in space to perfect ourselves only to return to the stars to find forgiveness (the liner-notes state that through “Powerlove” even “Lucifer, the eternal underdog” will be forgiven) and unite the heavens through “Powerlove.” But that’s the impression I get. And the song “Cherubic Hymn,” where two voices shout “we will learn that we are one with God and universal man, and then return with understanding to the world where we began,” seems to bolster that idea. What’s more striking is that Haack seems to think the change in spiritual consciousness that will have such a profound effect on humankind, and by turn “the Gods” and the rest of the universe, will come about, at least partially, through electronic communication, computers (children are even likened to programmable computers on the song “Program Me”) and electricity. He talks in terms of universal electronic communication that remind this listener a whole helluva lot of what we know today as the internet. And I can’t help but think, if more people used the electronic medium (whether it be the now commonplace synthesizer music that Haack basically birthed on this album or the universal electronic communication and information sharing tools we have at our disposal in the form of personal computers and the internet) to spread messages of love, sharing and personal connection as Haack suggested so many years ago that humanity could actually summon a force as powerful and affecting as the “Powerlove” he dreamt of.

“Electric to Me Turn”, an anthem dedicated to Haack’s “Powerlove” concept, opens ‘The Electric Lucifer’ like a bolt of lightning hurled by The Electric Lucifer himself to open the hearts and minds of the “Lucifer people” stranded here on Earth. This message of a love so powerful it can redeem even “The Devil” obviously echoes several millennia-old Gnostic heresies, with an obvious Hippie twist, while also sharing a bit in common with the Illuminati “history” of Graud as detailed in Wilson and Shea’s ‘Illuminatus!’ trilogy. And it’s certainly more appealing than the judgmental power trips offered by the traditional “big three” religions.

Haack had a vibrant career and released a plethora of albums, for both adults and children, from his pre-‘Lucifer’ debut in 1963 until his death in 1988.

Music is magick.